Everyone wants to talk about our current political, environmental-economic, and geopolitical malaise. Personally, at least in the US, I want to blame political parties. Grass roots democracy defenders point to the failure of our election system mostly in terms of closed primaries, which favor the extreme ends of party ideology, whose adherents then determine which candidates get on the ballot. Combine that with our winner-take-all system wherein elections end up being determined by a handful of swing districts in a handful of swing states. In any “safe” district or “safe” state, your vote doesn’t matter.1 So much for democracy.

Then there is capitalism. Free market defenders defend the free market to the hilt. But it’s a theoretical argument not based on “real existing free markets,” which don’t actually exist. (If you want to follow the one honest(?) attempt to recreate one, see Milei in Argentina.)2 What happens in really existing capitalism? Basically, inequality happens.3 Some other things may happen, too, like deep socio-cultural changes with the rise of rampant individualism.4

I’ve been reading James C. Scott’s Two Cheers for Anarchism.5 The preface alone is worth a long ponder, especially in the context of Scott’s other works, including The Art of Not Being Governed and Seeing Like a State, both of which I am also currently re-reading. Here’s the passage from Two Cheers I want to consider today. Apologies for length, but it’s worth quoting in full. The upshot is that there is no democratic freedom without relative (wealth) equality because the hyper-wealthy can and will use their money to manipulate not only markets, but politics.6

The point is simply that huge disparities in wealth, property, and status make a mockery of freedom. The consolidation of wealth and power over the past forty years in the United States, mimicked more recently in many states in the Global South following neoliberal policies, has created a situation that the anarchists foresaw. Cumulative inequalities in access to political influence via sheer economic muscle, huge (statelike) oligopolies, media control, campaign contributions, the shaping of legislation (right down to designated loopholes), redistricting, access to legal knowledge, and the like have allowed elections and legislation to serve largely to amplify existing inequalities. It is hard to see any plausible way in which such self-reinforcing inequalities could be reduced through existing institutions, in particular since even the recent and severe capitalist crisis beginning in 2008 failed to produce anything like Roosevelt’s New Deal. Democratic institutions have, to a great extent, become commodities themselves, offered up for auction to the highest bidder.

The market measures influence in dollars, while a democracy, in principle, measures votes. In practice, at some level of inequality, the dollars infect and overwhelm the votes. Reasonable people can disagree about the levels of inequality that a democracy can tolerate without becoming an utter charade. My judgment is that we have been in the “charade zone” for quite some time. What is clear to anyone except a market fundamentalist (of the sort who would ethically condone a citizen’s selling himself—voluntarily, of course—as a chattel slave) is that democracy is a cruel hoax without relative equality. This, of course, is the great dilemma for an anarchist. If relative equality is a necessary condition of mutuality and freedom, how can it be guaranteed except through the state? Facing this conundrum, I believe that both theoretically and practically, the abolition of the state is not an option. We are stuck, alas, with Leviathan, though not at all for the reasons Hobbes had supposed, and the challenge is to tame it. That challenge may well be beyond our reach.

Note a few things:

Wealthy parties get involved not only in the market as capitalists (they’re the main source of capital for investing), but also in politics, and they have a vast range of “huge state-like” tools at their disposal.

Wealthy parties have a strong interest in maintaining the status quo, the system that has generated their wealth. Ergo, existing political institutions will not provide avenues for change.

Dollars swamp votes.

Market fundamentalists, even when driven by theory alone (much less empirical reality as in “real existing free markets”), are already in morally questionable territory.

Anarchists — who are against any state as chief Extractor of resources (grain) and corvée labor (and this applies to all historical states up until the last couple centuries)7 — face a dilemma, because only the state can guarantee some level of equality, and hence, freedom and mutuality.

Scott doesn’t buy Hobbes’ argument for Leviathan, that the state must arise to protect humans from each other, humans who would otherwise be living in a state of nature where their lives would be “nasty, poor, brutish, and short.” This is because Scott actually sees a high degree of mutuality — i.e. social cooperation without hierarchy or state rule — amongst non-state people. Such cooperation is not, to be sure, at the level of Rousseau’s romanticized “noble savage.” Nevertheless, Scott concludes that some Leviathan may be necessary to counteract modern capitalism in its inequality-generating and freedom-destroying effects. And yet, what happened in 2008?8

It’s arguable, says Scott, where the democratic “charade zone” begins. How much inequality can be tolerated? Personally, I think the answer to that question depends a lot on what the wealthy actually do with their money.

When I asked myself that question: what do they do with it? — I originally came up with three main categories. First, they spend it on luxury goods, houses, yachts, buying up sports franchises, jet setting, throwing parties, I don’t even know what. This first use of wealth is probably what tends either to scandalize — or to provoke envy — amongst most regular people. But I doubt it’s actually a big proportion of the total. Second, they use it as capital for their own projects, or to found institutions, possibly even charitable. Here we think of Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, Bill Gates. In the past there was John D. Rockefeller and the other “robber barons” of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. This second kind of spending could be hugely beneficial for whole societies and economies, depending on. When free marketers and capitalists don’t worry (much) about inequality, this is what they’re betting on. Third, the wealthy do what Scott says they’ll do, which is to throw dollars as power into politics and political institutions to make sure the wealth keeps coming in, and the pot is protected from anyone who would take it away. My bet is that both of these second two areas of spending vastly outweigh whatever luxury spending is going on, certainly for the globally rich.

But now, what about the wealthy who are not like Musk or Bezos or even Bill Gates, who do seem to be managing their own wealth, for good or ill? Those three do what they do incredibly publicly. We all know what they’re up to and, given their egos, they react quite strongly in the court of public opinion. But what about the wealthy who rely on “financial experts” to manage their wealth for them? What about the heirs who inherit when the billionaires of the world eventually pass on? What about the remainder of the world’s wealth held by the minor rich and the middle class, as deposited in various sorts of mutual funds? Isn’t all of this managed by those same “financial experts”?

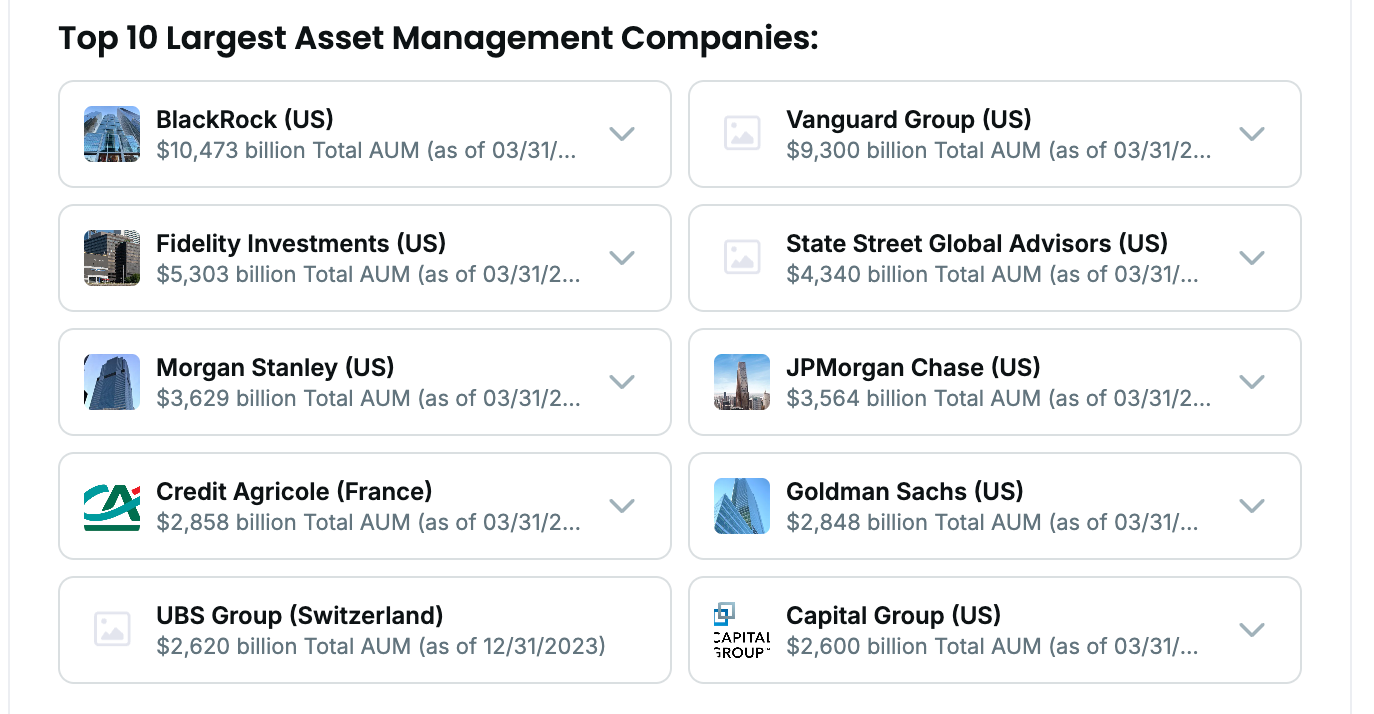

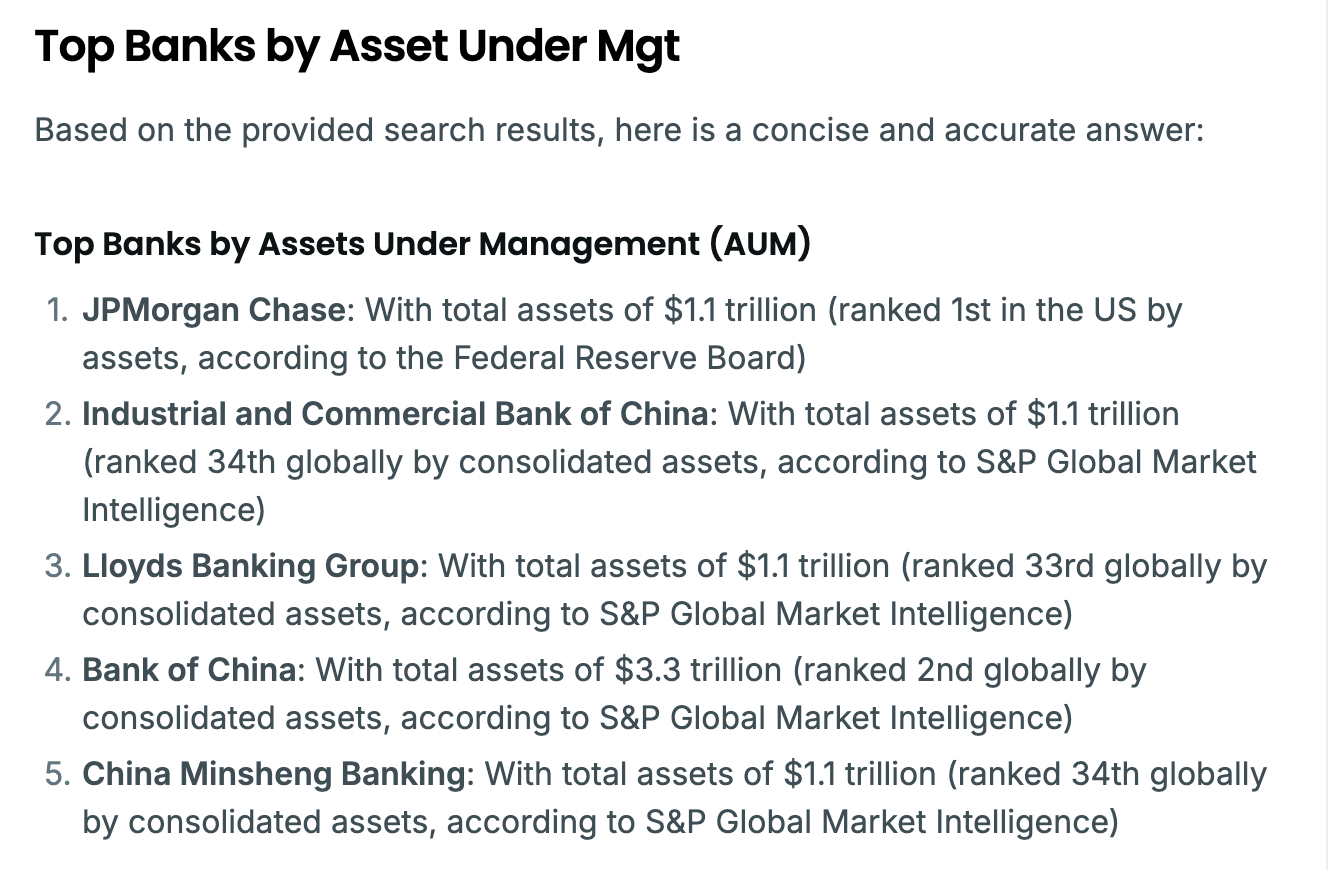

If we’re worried about the role of money and inequality manipulating not only politics, but capital and markets and whole economies, let’s have a look at who is actually managing the wealth. The technical term is, apparently, “assets under management.” Who in the world has the most AUM? And what are they doing?

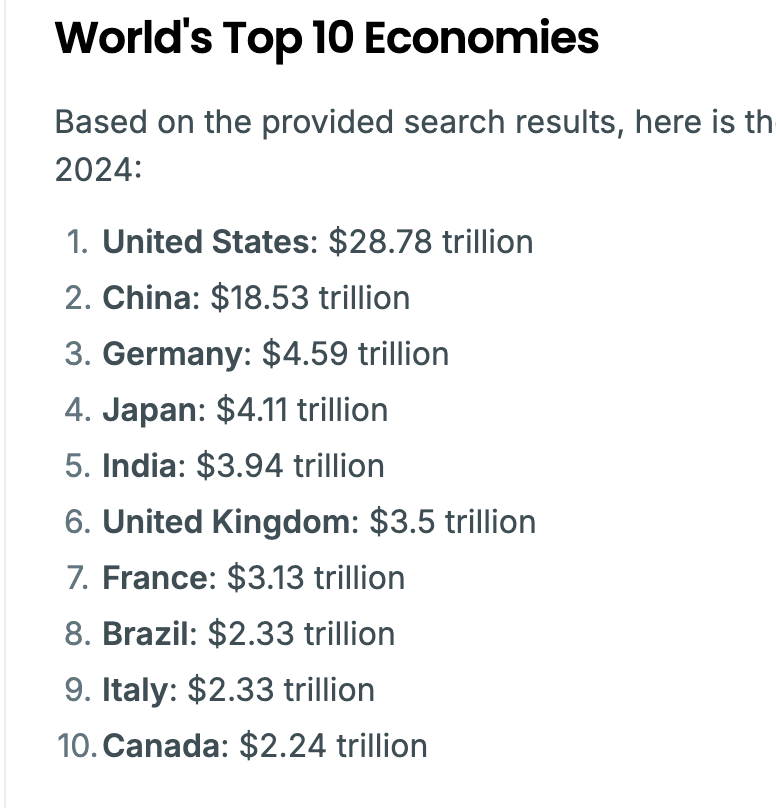

All this is beyond my competence to untangle, but I’ll leave you with just three screenshots I took this morning based on simple google searches. I can’t verify any of this data. But even if the order of magnitude is roughly indicative, it’s worth a very long ponder as to where we ought to be looking when we’re concerned about the failed or failing systems of the world: political, environmental-economic, and geopolitical.

And for comparision:

The world’s top asset managers and banks manage wealth at a scale greater than all but the very largest of countries. And if you combine even a couple of those asset managers, they out-manage even the wealthiest of countries.

Or maybe we ought to say that the wealth of the wealthiest countries simply is the combined assets managed under these state-like actors.

I’ll be reading more of Scott to see what we non-state, non-wealthy poor — we are genuinely poor by comparison, even if middle class — of the world might do in response.

See Nick Troiano’s Primary Solution book. You can also find him online talking about it everywhere.

The whole concept of “real existing x” has emerged on my radar, “real existing socialism” (or actually existing socialism, AES), for example. The relevant idea seems to be: you shouldn’t compare political economic theory with theory, or theory with reality, but reality with reality. What does real capitalism look like? What does real socialism look like? Real communism?

Thomas Piketty is probably the most well-known scholar investigating things empirically. See his many (heavy) books. Here’s a recent article. Or, google “inequality capitalism.”

This is for another day. Scott raises a key question that postliberals today use to fight against classical liberalism, i.e. (roughly) that a liberal society (democratic, capitalist) ends up undermining itself, primarily through rampant or overly ideological individualism.

It’s in the “Two Cheers for…” category of writing, foremost of which comes to my mind Two Cheers for Capitalism by Irving Kristol, a standard textbook in college economics classes in my era. I see E.M. Forster, the novelist, wrote a Two Cheers for Democracy, and Jedediah Purdy has a new book out: Two Cheers for Politics. The idea, of course, is that the system in question is far from perfect, but may be the best we’ve got. Winston Churchill famously said that, “Democracy is the worst form of government except for all those other forms that have been tried.”

Income or wealth inequality is measured using the Gini coefficient which compares the distribution of income or wealth across percentages of the population from lowest to highest. “A Gini coefficient of 0 reflects perfect equality, where all income or wealth values are the same, while a Gini coefficient of 1 (or 100%) reflects maximal inequality among values, a situation where a single individual has all the income while all others have none.” Here’s a 2024 world map: https://www.datapandas.org/ranking/gini-coefficient-by-country.

Scott says, also in the Preface, that, “of the roughly five-thousand-year history of states, only in the last two centuries or so has even the possibility arisen that states might occasionally enlarge the realm of human freedom. The conditions under which such possibilities are occasionally realized, I believe, occur only when massive extra-institutional disruption from below threatens the whole political edifice. Even this achievement is fraught with melancholy, inasmuch as the French Revolution also marked the moment when the state won direct, unmediated access to the citizen and when universal conscription and total warfare became possible as well.”

As an anthropologist, Scott studies mostly pre-modern states, whose main preoccupation in making “legible” those whom they govern is to be able to extract grain and other resources, and to conscript people for labor or war. He acknowledges that only in the last couple centuries has a possibility arisen that states might be interested in more than this, i.e. in governing for the sake of the welfare of their own people. And yet, even this is contingent on “massive extra-institutional disruption from below” to the degree of “threatening the whole political edifice” AND as often as not, any “success” will still be “fraught with melancholy” due to “direct, unmediated access to the citizen,” “universal conscription,” and “total warfare.” In other words, even if there’s a chance of the modern state doing something good, it is still a highly conflicted proposition.

I’m not sure why FDR’s New Deal is always cited as a great success, as the rise of the “welfare state.” But in comparison with pre-modern states, or in comparison with completely non-redistributive states that don’t care about or even actively exploit their people, maybe it’s a welcome improvement.