Philosophical Contenders

Some intriguing Anglo options -- I'm ignoring continental and Eastern philosophy for now

In a cursory search for ancient wisdoms that might still have contemporary influence, to help us with an anthropology for the Anthropocene, today I’ll list out a few philosophical contenders for you to explore.

There’s a whole huge thing with German philosophy (and French), collectively “continental” philosophy, but we’ll save that for another time. I’m also holding off for a moment on comparative East-West. Just because I’m presenting “Anglo” (British-American) options, and one honorary Frenchman, it doesn’t mean the roots don’t go back to the Greeks. As with anything western, they must.

(One other quick caveat. “Anglo” here does not mean analytic. I’m decidedly uninspired by that 20th c philosophical tradition.)

Effective Altruism (Utilitarianism)

A couple weeks ago I wrote about the recent OpenAI kerfuffle that also involved Effective Altruism. The very fact that a philosophical movement could muster that much direct influence on such a contemporary issue as AI should be enough to establish its potential. There are resources linked in that post, or you can just go to the Effective Altruism website as a place to start.

Everyone should become at least conversant with this approach to Anthropocene issues.

Modern Stoicism

The second philosophical contender that has to get a nod definitely goes back to the Greeks. Stoicism was wildly popular in the ancient world, and it’s an equally and increasingly pervasive modern “lifehack.”

Matthew Sharpe at The Conversation offers a nice introduction to this “unlikely reboot.”

We live in strange times. But few people could have expected today’s rise of a global movement of self-describing Stoic online communities numbering over 100,000 participants.

The author asks himself, why Stoicism? Why now?

It can’t be Stoic physics (completely outdated), so it must be the ethics, or even better, Stoicism’s proposed psychology — which is an anthropology, by the way, a theory of the human which, on Stoicism’s take, might be an all-too-tempting psychology for the Anthropocene, one I daresay we ought strongly to resist!

In any case, why Stoicism now?

The core of the answer has to be the enduring pertinence of Stoic ethics, especially as it has come down to us through the Roman Stoics Seneca, Epictetus, Musonius Rufus and Marcus Aurelius.

The pertinence hinges upon a few very simple, powerfully intuitive observations and principles.

These begin with Epictetus’ simple call to people to always distinguish between what is, and is not in our control. There is, at some basic level, no rational point in being unhappy about the things we can’t change. Learning to let go of these things, in order to focus on what we can affect—our own present impulses, thoughts, and actions—just has to be both philosophically astute, as well as a psychological boon.

(Source: Stoicism 5.0: The unlikely 21st century reboot of an ancient philosophy | theconversation.com)

You can find plenty of pop resources online for the new Stoic movement. If you’re serious, I recommend the accessible yet rigorous books of philosophical historian John Sellars.

Online encyclopedias of philosophy are also useful: IEP, SEP.

Or you could go straight to Epictetus.

Or… read the relevant chapter in John Cooper’s Pursuits of Wisdom, which leads us to our next section.

Philosophy as a Way of Life (& Hadot)

Cooper’s book is subtitled “Six Ways of Life in Ancient Philosophy from Socrates to Plotinus.” Here’s the blurb, which captures well this third, extra-worthy philosophical contender.

[Cooper’s book] is a major reinterpretation of ancient philosophy that recovers the long Greek and Roman tradition of philosophy as a complete way of life--and not simply an intellectual discipline. Distinguished philosopher John Cooper traces how, for many ancient thinkers, philosophy was not just to be studied or even used to solve particular practical problems. Rather, philosophy--not just ethics but even logic and physical theory--was literally to be lived. Yet there was great disagreement about how to live philosophically: philosophy was not one but many, mutually opposed, ways of life. Examining this tradition from its establishment by Socrates in the fifth century BCE through Plotinus in the third century CE and the eclipse of pagan philosophy by Christianity, Pursuits of Wisdom examines six central philosophies of living--Socratic, Aristotelian, Stoic, Epicurean, Skeptic, and the Platonist life of late antiquity.

The book describes the shared assumptions that allowed these thinkers to conceive of their philosophies as ways of life, as well as the distinctive ideas that led them to widely different conclusions about the best human life. Clearing up many common misperceptions and simplifications, Cooper explains in detail the Socratic devotion to philosophical discussion about human nature, human life, and human good; the Aristotelian focus on the true place of humans within the total system of the natural world; the Stoic commitment to dutifully accepting Zeus's plans; the Epicurean pursuit of pleasure through tranquil activities that exercise perception, thought, and feeling; the Skeptical eschewal of all critical reasoning in forming their beliefs; and, finally, the late Platonist emphasis on spiritual concerns and the eternal realm of Being.

Pursuits of Wisdom is essential reading for anyone interested in understanding what the great philosophers of antiquity thought was the true purpose of philosophy--and of life.

This idea that philosophy is not just an “intellectual discipline,” that at its root it is meant to embody an entire way of life, is extremely relevant for our purposes. There’s not just one philosophy, but many possible ways of life, even within the limits of classical Greece, each incorporating its own proposal for the best way to live as a human being.

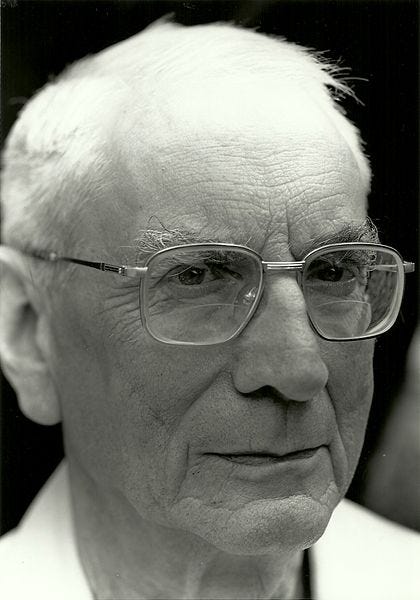

Cooper writes in the vein of reappropriating classical philosophical wisdoms for today as founded by Pierre Hadot. Hadot was a French philosopher who was a remarkable and influential classicist and thinker — and way of lifer — in his own right.

Pierre Hadot, classical philosopher and historian of philosophy, is best known for his conception of ancient philosophy as a bios or way of life (manière de vivre). His work has been widely influential in classical studies and on thinkers, including Michel Foucault. According to Hadot, twentieth- and twenty-first-century academic philosophy has largely lost sight of its ancient origin in a set of spiritual practices that range from forms of dialogue, via species of meditative reflection, to theoretical contemplation. These philosophical practices, as well as the philosophical discourses the different ancient schools developed in conjunction with them, aimed primarily to form, rather than only to inform, the philosophical student. The goal of the ancient philosophies, Hadot argued, was to cultivate a specific, constant attitude toward existence, by way of the rational comprehension of the nature of humanity and its place in the cosmos.

(Source: Hadot, Pierre | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy)

In case you might be skeptical about treating ancient philosophy as a smorgasbord which any seeker was expected to investigate, sample, and choose from, you might be surprised to know that even early Christianity was pleased to offer itself as a viable alternative at the same buffet table.

In its own mind, just as all the other philosophies did, Christianity thought itself the most convincing option. Justin Martyr is known as the original philosopher-saint. Here’s a link to Justin’s Dialogue with Trypho, which is a long, involved treatise that requires much commentary, but do have a look at the opening chapters.

Contemporary religious engagement with the PWL tradition is alive and well, as here: Philosophy as a Way of Life | University of Notre Dame.

Tyler Cowen’s GOAT :)

Tyler Cowen, the prolific economist of Marginal Revolution fame (you can also check out his and colleague Alex Tabarrok’s online economics “university”), went in search of the Greatest (O)economist of All Time or GOAT.

(English “economy” comes from the Greek oikos and nomos and means “law of the house.”)

Was GOAT for Tyler Adam Smith? Actually… not.

Cowen didn’t publish his GOAT book via normal channels, but as an intriguing “generative” book complete with an incorporated AI trained on Cowen’s own prolific writing. (Try it.)

The book’s concluding chapter evaluates Cowen’s short list of potential greatest economists (Hayek, Keynes, Malthus, Friedman, and Smith), and ends up with the following. Note how important it is to keep a set of evaluative criteria in mind.

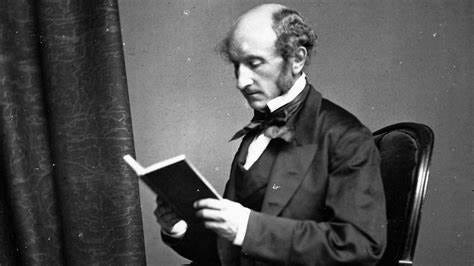

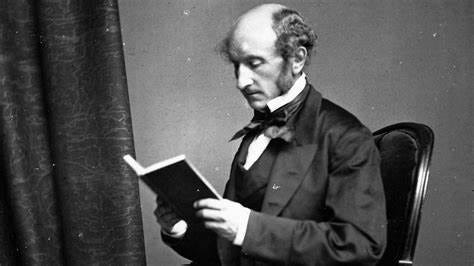

Now let us turn to the remaining GOAT candidate, namely John Stuart Mill.

Although he is not a common candidate for a GOAT designation, Mill has a number of arguments in his favor. First, he had a broad sense of economics, very much in accord with how economics is practiced today. When it comes to “topics considered,” I give Mill first place amongst the GOAT contenders. His Subjection of Women is one important contribution along those lines, but hardly the only one. He also was a major contributor to politics, philosophy, the humanities, and historical thinking.

I also give Mill first place for depth of thought and insight. No single book chapter can communicate fully that depth and insight, especially when it is written by a thinker (me) who is less deep than Mill was. Still, I recommend that you all read Mill through and see if you might agree with me. Hardly any contemporary economists have done this, and Mill is somewhat neglected even among historians of economic thought, at least compared to the other GOAT contenders. He attracts more interest from say political theorists and philosophers.

In my admittedly subjective view, Mill was “the best thinker about the world” of all the GOAT contenders.

For Mill to be a serious GOAT contender, you have to take the view that the subject matter of economics is not entirely well-defined, and that there is some broader entity, consisting of both social science and the humanities, that is prior to economic investigation. Mill was the master of that broader entity.

That all said, there are some serious negatives for Mill as GOAT.

First, he wrote a very long book on political economy. It was very good for the time… In terms of original ideas, in economics narrowly construed, Mill is not close to the top.

Second, on empirics Mill did not do statistical work and that also limits his GOAT claim. Still, he was prescient on method and causal inference, and he was a remarkably keen observer of the world around him.

Third, while Mill was a much better economist than Adam Smith he is far from perfect on that score and he had no explicit access to marginalist thinking… That said, Mill was very likely the greatest economist of his time, and the greatest pre-marginalist economist, so you can give him some support on this issue nonetheless.

Of all the GOAT contenders, Mill is my clear favorite as a thinker, but I cannot pretend that he has vanquished the competition to deserve a clear first place as the Greatest Economist of All Time. He does not. Still, since this is my book, his is the one name I want you to take away from this endeavor, and if that makes him an informal winner of sorts then so be it.

(Source: GOAT book, chapter 9)

For a variety of reasons, not just Cowen’s award, I’ve been re-reading Mill recently, just a sampling. His complete corpus is huge! He is indeed impressive, even beneath all his Victorian prose. What I particularly like is his vision of modern humanity, a liberal vision that encompasses not only “classical liberalism” and “progressivism,” but perhaps the best post-Enlightenment worldview of any Anglo philosopher of the past couple centuries. To compare him to Cowen’s alternative greats, all of whom are apologists for (economic) liberalism, Mill has by far the most sympathetic and optimistic view of the human project overall.

The liberal vision, in both classical and progressive guises, has recently come under attack — more or less rightly so, in my view. Although, I am heartily disinclined to buy uncritically any of the current batch of postliberal critics. (More on that coming soon.)

Before going to that debate, however, reading Mill firsthand makes for a bracing preparatory exercise. If you’d like to imbibe on your own, try chapter 2 of On Liberty, “Of the Liberty of Thought and Discussion.”

Tip: Don’t stop until you get to this passage about three quarters of the way through the chapter. Here you will find Mill’s own defense of what (I think) will be the increasing need to hear both liberals and their emerging postliberal critics. I’ve no doubt the liberals (genuine ones, at any rate) will show themselves the more capacious thinkers, and this open-minded capacity is Mill’s special genius.

In short, I agree with Tyler. I vote Mill for GOAT. :)

It still remains to speak of one of the principal causes which make diversity of opinion advantageous, and will continue to do so until mankind shall have entered a stage of intellectual advancement which at present seems at an incalculable distance. We have hitherto considered only two possibilities: that the received opinion may be false, and some other opinion, consequently, true; or that, the received opinion being true, a conflict with the opposite error is essential to a clear apprehension and deep feeling of its truth. But there is a commoner case than either of these; when the conflicting doctrines, instead of being one true and the other false, share the truth between them; and the nonconforming opinion is needed to supply the remainder of the truth, of which the received doctrine embodies only a part.

(Source: John Stuart Mill, On Liberty, chapter 2.)

The rest of Mill’s short discussion of the “commoner case” could be mandatory reading for everyone concerned today with our overly polarized political scene.