Arendt’s tripartite division of human activity — the vita activa — into labor, work, and action, when taken along with its counterpart in thinking — the vita contemplativa (which in The Life of the Mind also has its own three-part division into thinking proper, willing, and judging) might be used as a conceptual model for building a practice of lifelong learning. I’ll propose that Arendt can serve as a valuable conversation partner for what we’re all about here at Pose Ponder.

We might call it world-building for lifelong learning, for the Anthropocene.

Or we might call it the development of a techne, a framework of knowledge and practice, which would be a type of artifice, a cultural or institutional table — understood both literally and metaphorically — around which humans can gather in a community of practice, to try to live a good life in general and especially to engage in political action.

In a previous post, I suggested that part of a Pondercraft techne would be to consider four Life Areas, as I called them. Paying adequate to each would lend balance to human life. It would, in Arendt’s terms, allow humans (in the Anthropocene) to honor the fundamental human conditions by which they live on earth, which are given to them 1) by the earth itself, as biological beings, 2) by the world, a place of durable things, institutions, and cultural artifacts, into which humans enter at birth (their natality) and in which they sojourn from birth to death, and 3) by the public realm, in which humans appear when they engage in political action.

Arendt in her book The Human Condition is fundamentally about creating and protecting spaces of freedom, where humans both 1) respect what has been given as these three main conditions of human life; yet also 2) prevent any relapse into totalitarianism, a state of things that has become a historically new possibility (an actuality Arendt herself experienced). Totalitarianism destroys above all the human condition of plurality and the possibility of action. It destroys all spontaneity and individuality of thinking and acting, and thus human freedom.

Putting together the three givens of the vita activa and the two deep motivations driving Arendt’s work, a central observation is to see how critical PLACE is in her scheme, where places or spaces situate human activity.

Humans as biological beings labor in private, according to Arendt, in households, to provide and secure the daily necessities of sustaining life and preserving the human race through raising families.

Humans as worldly beings are born as newcomers into a world that came into being before them, made by prior human work (artifice). The world will continue after each human life has come and gone. Humans have the possibility of maintaining this world, of adding to it through their own creative work, both material and cultural, and of welcoming and guiding newcomers who enter after them.

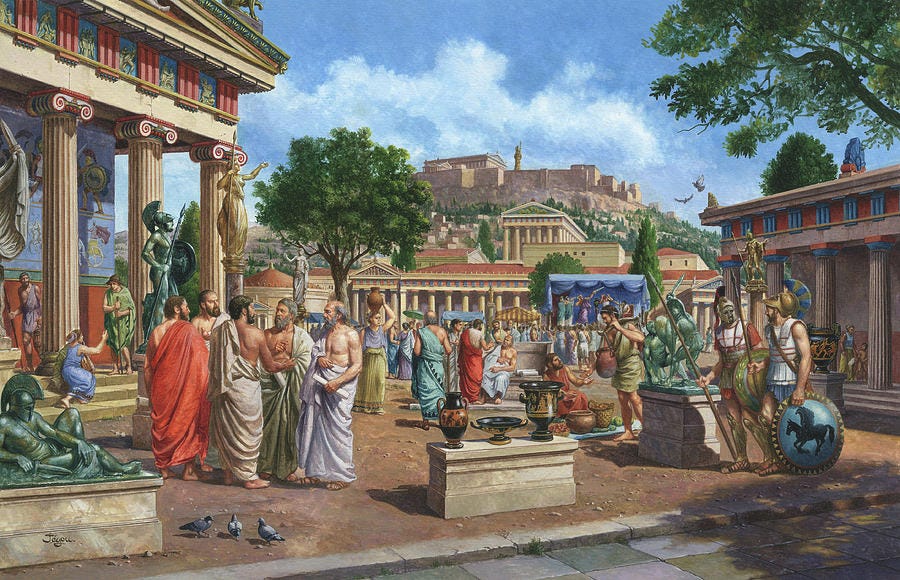

Humans also have as part of their innate condition the quality of plurality, which provides for the possibility of appearing in the public realm (think of the Greek agora or the Roman forum or an American town hall meeting) to engage with each other, with peers on an equal footing — yet in a diversity of experience, thought, and personality — via political words and deeds = political action.

Plurality is the condition of human action because we are all the same, that is, human, in such a way that nobody is ever the same as anyone else who ever lived, lives, or will live. (Human Condition, 8)

So in sum:

Labor happens in the private realm of the household.

Work maintains, adds to, and introduces newcomers to the world.

Action is words and deeds emerging from pluralistic participation in the public realm.

The public realm is the place most at risk, as the space of freedom that comes under attack (displacement, loss) with the rise of totalitarianism. Arendt calls this the “rise of the social,” where “the social” is distinct, in her terminology, from the world or the public. The social is the rise of the masses (as such), of homogenous human crowds smushed together without “tables” to “separate and relate them” to each other in plurality. The social, taken as a "totalizing force (as in the “totality” of totalitarianism), balloons ever larger, expanding, taking over an ever widening expanse of space or place, usurping both private and public realms and destroying their proper human activities. The durable world, with its arts, is transformed into a new economic space. It’s completely “economized” with ever-faster production and consumption, work turning (back) into labor, everything becoming ephemeral and (effectively) waste.

We might say today, extending Arendt’s observation, that an entirely economized social realm is like an all-pervasive linear, non-circular economy — a hamster-wheel of continuous production and consumption, whether of goods, services, or content (information, cultural artifacts) — where there is no durability even in the sense of circular renewal or re-purposing anything used or useful. There is no re-cycling, re-furbishing, re-fabrication, much less the creation and endurance of anything quasi-permanent, stable, safe or secure.

Earth and world no longer provide a home for humans. (So it becomes ever-easier to think about leaving it.) There is nothing left that approaches “immortality,” in the sense of long sustained memorials continuing through time and history. However brief and fragile human lives were in all prior ages, there had always been the hope of these limited types of permanence.

Restoring balance, according to Arendt, would mean restoring the proper places or spaces of fundamental humans activity, while respecting the human conditions of earthly and worldly life. Balance would require putting the world back together, reclaiming it from the “blob” of the social.

I developed my short list of Life Areas completely independently of any thought to apply Arendtian concepts to the project of lifelong learning. It was born out of simple commonsense reflection. But now I am considering how Arendt’s fundamental human places and activities might relate.

Here is my original list. The glosses on each call to mind what would be needed as part of a techne for lifelong learning.

LA #1 — Personal Life — individual habits (practices) and attention to home, family, and immediate neighborhood

LA #2 — Work Life — making a living, job, career, day to day occupation and vocation

LA #3 — Travel — a system for getting beyond your bubble and being exposed to the wider world

LA #4 — Civic & Political Participation — giving back, reaching out

One might observe, right off the bat, a clear correspondence between

LA1 (personal, home) and Arendt’s household, private realm, in which labor takes place to provide life sustenance and maintenance.

LA2 (work) would correspond to work in the world, although it also has clear affinities to the rise of the economized social realm, where production and consumption rule, and work has become “labor” (a la Marx) and what one must do to “earn a living.”

LA4 (civic and political participation) comes very close to Arendt’s call for action in the public realm. She was more concerned with making an “appearance” there (with historical ramifications, showing one’s unique personhood in plurality), performing memorable, story-worthy words and deeds. I am more concerned with making a contribution, reaching out, giving back (maybe my thinking was more affected by the transactional). But it’s close.

That leaves LA3, travel.

My thought was that travel is essential to lifelong learning because it breaks you out of the everyday and helps to see beyond inherited assumptions and lifeways. Education should not be entirely parochial. It’s inherently open.

Arendt, on the other hand, was deeply concerned with the places of human life making up our earthly, worldly home. She was a forced migrant, a refugee, for many years lacking citizenship or the protection of rights, living in exile (if not the camps).1 But I learned something rather astounding at my class this week. In her famous interview with Gunther Gaus in 1964, Gaus had introduced her as a philosopher, and she vehemently protested this in favor of being called a practitioner of “political theory.” (The exchange comes at the very beginning of the interview.) What is this “theory”? What is a political “theorist”?

The underlying term is the Greek theoria, which traces directly to the ancient and medieval counterpart of the vita activa, the vita contemplativa. “Contemplative” translates from Aristotle’s bios theoretikos in Greek. To contemplate is to theorize, which means a special sort of seeing-thinking. Arendt is a seer-thinker of political action. The object of contemplation of the vita contemplativa is politics and the realm of the political. It’s not contemplation of some eternal reality; it’s to quite literally to theorize our action, to “think what we are doing.” (HC, p. 5)

But that’s not all. The connection to ancient Greek practice runs much deeper — and further afield.

The original Greek practitioners of theoria were the theoroi who would theōreō (θεωρέω), the verb form. There was a very specific cultural role and practice, vital to the life of ancient Greek city-states.

The theoroi (Ancient Greek: θεωροί or θεαροί) in ancient Greece were sacred ambassadors, messengers sent out by the state which was about to organize a Panhellenic game or festival… theoroi meant something like "observers" and they were envoys sent by city-states to consult oracles, to give offerings at famous shrines or attend festivals.

The verb thus meant:

to be sent (as a θεωρός (theōrós)) to consult an oracle

to look at, spectate, observe

to contemplate, consider (of the mind)

(abstract) to speculate, theorize

(Sources: Wikipedia, Wiktionary)

The vita contemplativa, taken to its earliest Greek origins, means to be a political observer and a traveler to foreign realms to see what is happening there, and to report back. This is what Plato discusses in the allegory of the cave when the philosopher strikes off his chains and ascend to envisage the realm of the forms — and comes back to free his fellows. This is what Aristotle does when he sends for copies of the constitutions of all the Greek city-states. This is what Arendt does when she goes to Israel to observe the Eichmann trial and report back.

My original intention in incorporating travel as a third life area for lifelong learning — establishing it as a life practice at a high level — was based on my own experience, on how much I learned personally from studying abroad in college, from living abroad, from traveling in Europe, Asia, Africa, from trialing life as a short-term digital nomad. From my experience, there is almost nothing more formative in terms of acquiring new and wide-ranging perspectives on life than travel. Travel as included at a fundamental level in my techne of lifelong learning started out in this broad and completely vague sense. But I’ll happily hold it together as of a piece with Arendt’s theorizing.2

Travel as LA3 surely could play the part of a new vita contemplativa for the Anthropocene, together with labor for life (LA1) and work for better world-building (LA2). If it focuses sufficiently on the places and spaces of vital and free human activity the world over, it could surely also be an essential component of political theorizing, in the service of political action (LA4).

Balanced lifelong learning for the sake of creating and protecting human spaces of freedom, while deeply respecting the human condition as given by the earth and the world, of engaging in the lives (vitas) of human activity and contemplation, may after all be a matter of getting these four Life Areas right.

Arendt’s conceptual theorizing(!) in The Human Condition may after all provide a most vivid, robust, and satisfactory model for fleshing out what living a vital — and good — human life, in a fundamentally new and risky era, could mean.

Giorgio Agamben, whose work draws deeply on Arendt, centers his reading of all of history and his own reading of the human condition and the political, around the problem of the concentration camps. See his Homo sacer series.

This is especially true because I have done research and work elsewhere on the phenomenon of the spectacle as theologically and liturgically important, possibly as another variety of essential (political? economic?) kind of human space, activity, and contemplation.

Tracy, I think I want to play Devil's Advocate a bit. Nothing that follows is meant to denigrate anything you have written.

I find you category "Travel" as a life area difficult. If you mean it metaphorically, that is one thing; if you mean it literally, that is something else. Travel is wonderfully broadening for some, but for others it seems to make no difference (some of the narrowest-minded people I have known were among the most widely travelled, while some of the broadest thinkers hardly travelled). For many it is difficult or nearly impossible due to health, disability, family commitments, or economic insecurity, let alone for political reasons. We might also think about the long history America, in particular, has with well-traveled veterans who return alienated and hating a liberal, diverse society. That's been happening for at least a century.

I feel that to focus on "travel" - even if for historical reasons may be a problem. Is this really what the category should be? It seems like what you are talking about is really about an expanding worldview, and that might happen in a number of ways.

Is there a better term for this, something broader? It seems to me that imagination and empathy, curiosity and desire (to learn, for something new, for experiences) are the keys.