Yesterday I outlined three ways the Breakthrough Institute applies overall values of decoupling and intensification to address Anthropocene problems: in demographics (urbanization), agriculture, and energy. They go so far as to declare their allegiance to these values by publishing a Manifesto!

At heart, I’m a pragmatist. I like things to work. Truth, yes, beauty, yes, goodness, yes. These ultimate values are certainly not unimportant (certainly not!). But, because any concrete particular version of them is so contested today, they are hardly easy to bring to bear in on any practical matter. You’re involved in controversy about “first principles” before you can even start to apply. A pragmatist might bypass it all and simply stick with expediency. Does it work? Does it actually help to resolve an obvious problem at hand? Does it present as acceptable, to reasonable people regardless of prior commitment or creed?

At some point, however, expedience starts to wear thin. One is thrown back onto more complex philosophical questions. These can be formulated as religious or theological questions for anyone who takes deep western traditions seriously (most historical traditions are religious), or ancient cross-cultural wisdoms (these tend to be religious, too), or who has any sense that there’s a normative order beyond what humans make up for themselves.

This Beyond-the-Human norm, whatever it is, might be something that inheres in nature, or it might be at some teleological remove, i.e. that which nature might be “for” to put it in causal, temporal, Aristotelian terms. Or to be more Platonic about it — more spatial than temporal — it could be that worldly realities are a bit shadowy and imperfect compared to their ideals, whatever those are and wherever they might be found (“ascended to”) and contemplated.

I’ve mentioned previously that, for simplification’s sake, one might think along roughly four dimensions (call them A1, A2, A3, A4) about the Anthropocene: 1) megatrends; 2) land and water use (case studies); 3) circular economy (or not); and 4) “the human factor.” If megatrends describe where we’ve got to over time, while our usage of space and place, along with our economic processes, give an indication of how we got here, there’s still the question of what we might do about it.

That “we” in “what we might do” calls forth the normative dimension of the Anthropocene. We anthropoi of the Anthropocene are called beyond mapping and description, beyond mere analysis of human impact and systems, to agency both ethical and political. Once arrived in a realm of choice, if we find eventually come to find pragmatic expedience rather thin, A4 will inevitably involve us in deeper matters of philosophy and religion.

Luckily, every philosophy, every religion, every deep tradition and ancient wisdom has its anthropology, its theory of the human.

Over the next few daily posts I want to begin to explore some resources I’ve discovered that could — or rather should, if they are traditions as wise as they claim to be — shed some light. Classic anthropologies for the Anthropocene, as it were.

Quite frankly, I’m actually not at all sure that they will. Can age-old traditions and wisdoms, developed and arranged to bear on radically different times, places, and era — a radically different geological era — really speak?

That’s the Question or Tension at the heart of the inchoate quality of the Daily Inchoate.

In any case, probably we’ll start tomorrow with a couple easily identifiable major religious traditions, whose main spokespersons have hardly been silent.

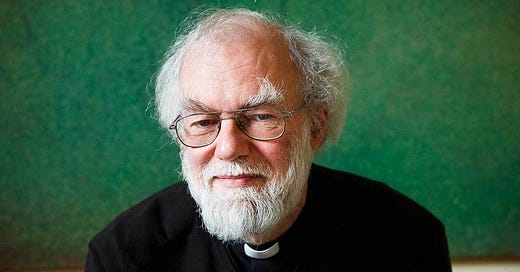

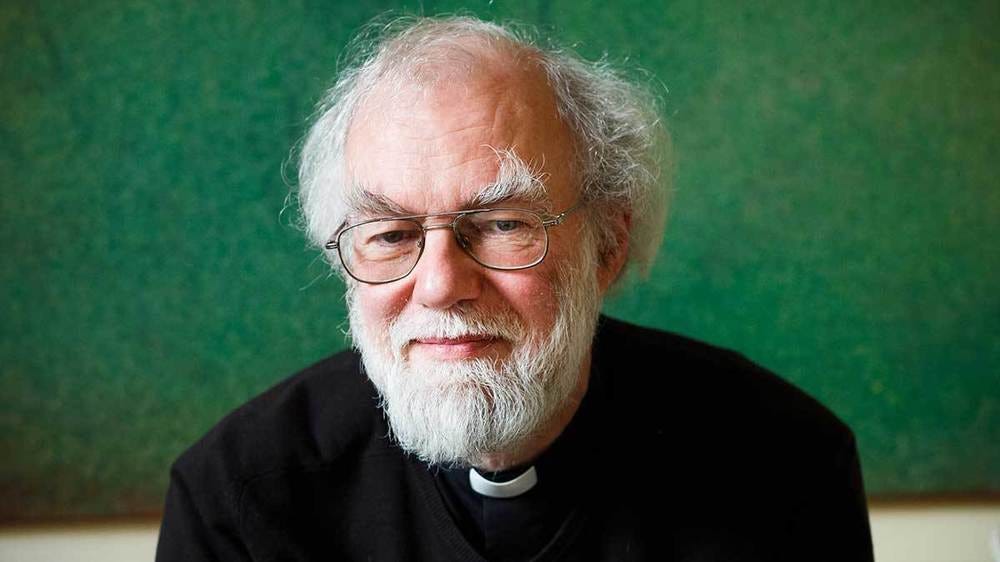

As a warm-up, however, exemplary in his candid acknowledgement of how difficult it is for a major religious leader to address complex (Anthropocene) issues, I’ll share the introductory apology of Rowan Williams, erstwhile Archbishop of Canterbury (the chief Anglican bishop), from his book Faith in the Public Square.

I’ve heard Archbishop Williams speak in person several times. I’ve even been introduced to him when I was a student (later on, faculty) at a prominent Eastern Orthodox Christian seminary. One can only admire his scholarly erudition, his good humor, and above all his deep concern for contemporary struggle: of human persons, of human societies, even of the planet (creation) as a whole.

Here’s Rowan.

Every archbishop, whether he likes it or not, faces the expectation that he will be some kind of commentator on the public issues of the day. He is, of course, doomed to fail in the eyes of most people. If he restricts himself to reflections heavily based on the Bible or tradition, what he says will be greeted as platitudinous or irrelevant. If he ventures into more obviously secular territory, he will be told that he has no particular expertise in sociology or economics or international affairs that would justify giving him a hearing. Reference to popular culture prompts disapproving noises about ‘dumbing down’; anything that looks like close academic analysis is of course incomprehensible and self-indulgent elitism. A focus on what many think are the traditional moral concerns of the Church (mostly to do with sexual ethics and family issues, though increasingly including ‘end-of-life’ questions) reinforces the myth that Christians are interested in only the narrowest range of moral matters; an interest in other ethical questions invites the reproach that he is unwilling to affirm the obvious and sacrosanct principles of revealed faith and failing to Give a Lead.

Well, archbishops grow resilient, and sometimes even rebellious, in the face of all this.

(Source: Faith in the Public Square)

Good archbishops do grow rebellious! He is one of far too few religious leaders who is indeed interested in more than “the narrowest range of moral matters.” If anyone can address our Tension, he is a likely candidate.

He also affirms my conjecture that one can be a non-expert — but hardly disinterested! — in contemporary science, technology, economics, and so on, yet still potentially have something to say. In his case, uniquely, what he can (and does) say comes forth from 1) an astoundingly wide-ranging personal and professional study of the best (ancient) wisdom traditions the world has to offer; along with 2) a completely immersive firsthand experience at governing in the thick of contemporary affairs.