For weeks (!) I’ve been leading up to writing about this book, Climate Leviathan, by Joel Wainwright and Geoff Mann published in 2018. Ultimately it should be read in concert not only with John Gray’s New Leviathans, but also Hobbes’ original Leviathan, Carl Schmitt on the state of emergency and friend/enemy distinction, as well as Naomi Klein’s This Changes Everything. Plus: Gramsci on hegemony, UN climate documents, and a variety of other interlocutors as featured in the book. That’s a tall order. With or without adequate preparatory reading, it’s an important, if dense and difficult, book. It proceeds through a rich and rigorous logical analysis and synthesis and is well worth an intellectual wrestling match.

The book comes from writers on the Left. I would argue, actually, that they are recognizably quite traditionally Left, if that can be considered apt. Their political home is activist, justice-seeking, “Occupy”-aligned, protest-aligned, social Movement-building Left — in this case, Climate Justice Movement.

“Traditional” though they be, they are yet calling for something new to come into the world, with eyes wide open. Like Arendt.

Political-Economic Futures

When talking about climate (and one could easily substitute other Anthropocene concerns, from biodiversity loss to land-water use, or circular economy), it’s not just about science, or technology. It’s about economics, specifically capitalism, and about politics, specifically nationalism, globalism, sovereignty, hegemony; and about the active role dominant interest groups and controlling elites will play, the economically and politically powerful. Justice for the poor and vulnerable, who as the climate crisis looms will be the ones to suffer, whose suffering will be rationalized by those elites as the unfortunate, but necessary sacrifices required to “save the planet,” is in reality what’s at stake in these times of emergency.

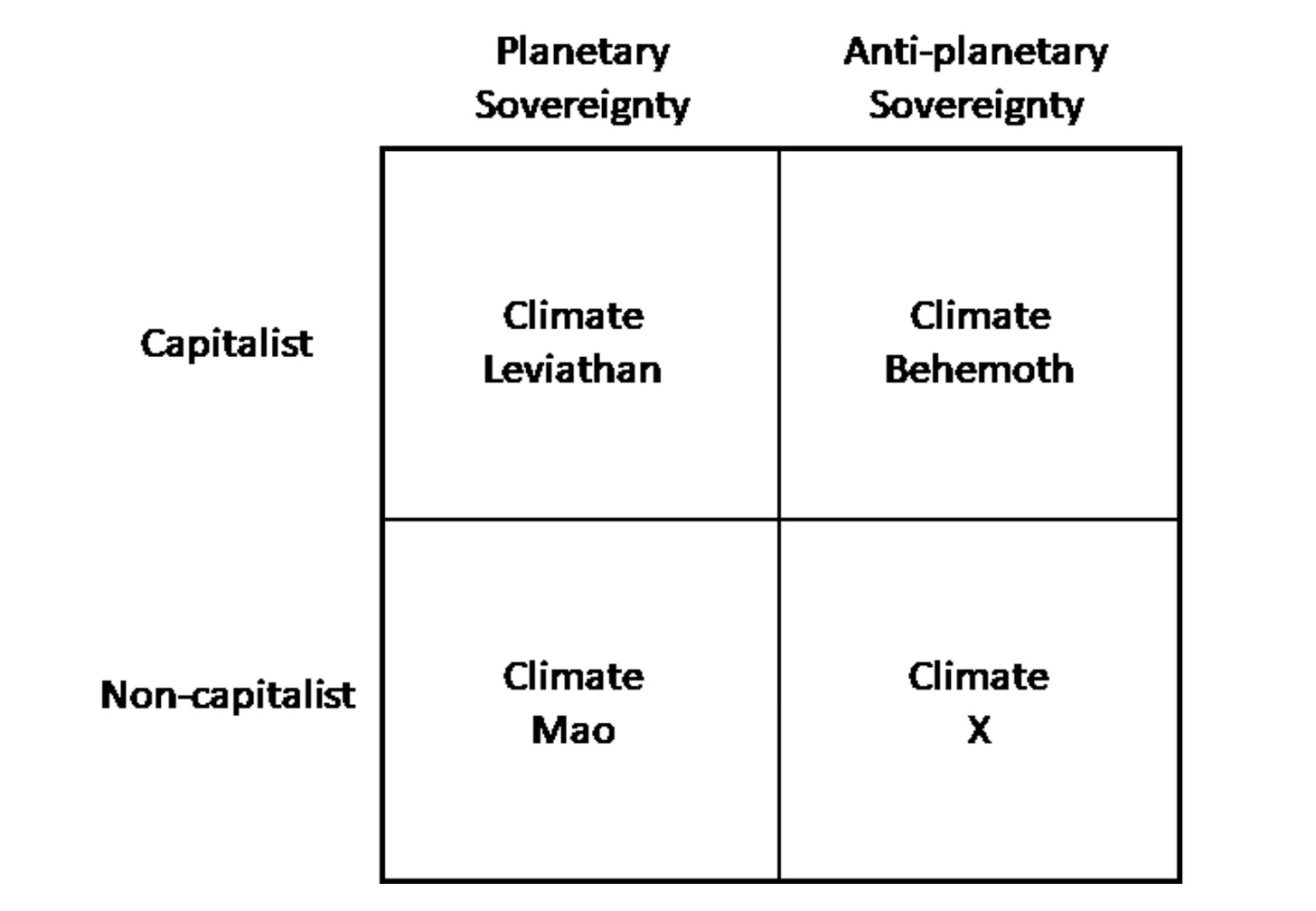

In our present “conjuncture” (situation), the Question, then, is one of possible political and economic futures. Capitalism or no capitalism, on an economic dimension, and planetary sovereignty or no planetary sovereignty, on a political dimension, thus define the four possible “social formations” a speculative politics can project. The authors name, revealingly, each quadrant:

A “planetary sovereign,” by the way, is basically a political-economic power elite that can establish some kind of globally controlling hegemony.

The Four Options

Climate Leviathan is the most likely scenario for our planetary future, and it’s already in process of establishing itself via the work of global elites in the UN, giant corporations, dominant governments and states, and organizations (I would argue, like the WEF, but the authors do not mention it). In a state of climate emergency, where mitigation is no longer feasible, adaptation will be the best we can do. Someone will need to take charge (gain sovereignty, hegemony), on a global level, and some will survive (even thrive), current economics and interested parties and actors will continue in “green capitalist” modes, and the poor and disenfranchised will, well, suffer and end up bearing most of the planet’s suffering — along with future generations (and the planet itself and, presumably, all its other living creatures). (It’s a political manifesto, not an ecological one.)

Climate Leviathan is the biggest, strongest game in town, and it’s the foe to beat, if that’s possible, for any authentically left, activist, protest-oriented, anti-capitalist, anti-nationalist (anti-imperialist, anti-colonialist) Climate Justice Movement like the one hope proposed by the authors: Climate X.

Climate Mao and Climate Behemoth get minimal attention. I would say they need much more, given the importance of China to global political futures (Climate Leviathan vs Climate Mao); and given the increasing move in Europe and the west rightward to populism and postliberalism. The authors, writing in 2018, mostly look retrospectively to Paris in 2015, although they acknowledge the rise of Trump in 2016. Climate Behemoth, for them, stands primarily for a reactionary right that wants to maintain capitalism, but is anti-elite and anti-globalism (anti-planetary sovereignty). The book’s treatment of both Climate Mao and Climate Behemoth, a bit short shrifted, needs updating. What’s going on with Climate Behemoth, especially, could stand more constructive engagement with Climate X, those far ends, ultimately conjoining (?), of far right and far left.

Assessment

Most of the book (Part Two, chs. 3-6) is taken up with a critique of Climate Leviathan, and true to Marxist critical spirit, it is in some ways the most valuable part of the book. (Marx himself, ostensibly, was far better at critiquing capitalism than at coming up with a decent plan for replacing it.)

The overall project of the book (Part One, Part Three), to identify useful political philosophical sources, Hobbes, Schmitt, Gramsci, Marx, Adorno, Klein, and others; and to push for much deeper consideration of the goals and rational of activism and radicalism on economic and political fronts; is also quite compelling, however Left it may be (very Left).

The positive agenda to think towards Climate X, towards a new Manifesto with three “new” principles (they’re hardly new) for an activist climate justice movement is suggestive, but problematic. That’s hardly a surprise, since it’s the most difficult task. The authors call for equality (against the inevitable inequalities of capitalism), diversity and inclusion (against overly sovereigntist “thin” democracies), and solidarity with the communities, peoples, and ways of life on the sacrificial chopping block of Climate Leviathan (ch. 8, sect. 2). All this resonates, of course, especially the desire to find a path between utopianism, realism (which concedes to Leviathan), and pessimistic nihilism. I do think the author’s heads and hearts are in the right place, and they are courageous enough to seek out a real solution, not a mere compromise, or a noble but ultimately failed (yet self-congratulatory) attempt, going forward.

I do wonder about their commitment to “revolutionary” activism (they don’t call it that), meaning basically popular protest movements combining climate justice with social justice (pro-indigenous, anti-colonial, anti-nationalist). Engaging with Arendt on revolutions would be fruitful, particularly her juxtaposition of the American and French, each with a different central concern: the American Revolution to put forward-looking political infrastructure in place vs. the French Revolution mounting a revolt against inherited class privilege and (corresponding) economic woe. Arendt sided with the Americans and criticized the French.

Mitigation vs Adaptation

What may ultimately be the most constructive contribution of the book is its hard look at mitigation vs adaptation. There is no need to abandon all hope of (any) mitigation, even if we have utterly failed to prevent planetary warming to more than 1.5 degrees. But there is surely the need to face squarely the hard economic and political realities of the coming regime(s) of climate adaptation, i.e. learning to live with it. The world’s societies, economies, and polities are going to Adapt. The Question is: to what? and to whose benefit?

Certain people for sure are positioning themselves for survival, or even continued thriving, in whatever the upcoming regimes will be. They have the resources — and will ensure they keep hold of the resources — they need to do so. Recognizing this as contemporary political climate reality is perhaps the most convincing argument of the book. But I would still like more clarity regarding technology, economics, and politics, and their interactions. The current internationalist (UN) politics may indeed have failed to mitigate — thereby clearing the way for elites to secure their own adaptation through green capitalism and a new kind of sovereignty — but technology is evolving quickly, and new players are gaining power.

Adaptation on all three dimensions (technology, economics, politics) is also not the prerogative of elites only. The poor and vulnerable — peoples, communities, ecosystems, species, lands and oceans at risk — may indeed have fewer economic resources, but some types of technologies spread quickly, and political resources are themselves potentially dwindling in decadent “progressive” societies, however rich (or, rather, however rich narrow elite slivers of their populations are). The world is moving to the right, populist, reactionary, postliberal, and religious: Behemoth. Are there political resources here for the poor and disenfranchised? Contemporary right political and economic appeals are certainly demogogic.

On the other hand, books like The Dawn of Everything (or even the studies of James C. Scott on “anarchic” societies living on the periphery) contend that what may be the most hopeful scenario is to pay attention to buried, marginalized wisdoms hidden away from the “civilized’ mainstream. What vulnerable, pre-liberal societies — to the extent they still exist — can offer are genuinely unique anthropological alternatives. I am a bit skeptical, because we now live in mass societies: where are you going to put 8 billion people on a marginal fringe? and in complex, post-industrialized, urban-yet-globalized Anthropocentric centers, with all that implies. What brand of wisdoms can speak into this, if any?

Nevertheless! We shouldn’t discard any widening of the human imagination. As long as we don’t forget the hard-won political victories gained over the modern period, genuinely novel ethical and philosophical victories, which, admittedly, have gone hand-in-hand with the rise of the very technological and economic developments that make up our Anthropocene crisis, there is plenty to learn from a long human past and from “lost” human geographic diversity.

As I said, Climate Leviathan is an important, dense, difficult book, but its clear logic, vivid case studies, and compelling philosophical analyses make it recommended.

If you do read, please come back and…