Adler on the Problem of Education (Part 1)

Reacting to Mortimer Adler's diagnostics and prescriptions

You know how on YouTube there’s this thing called “reaction videos”? It’s where somebody watches some other third-party video for the first time, and they record their reaction to it. I guess it’s similar to “unboxing” videos. A YouTuber records their own reaction as they go through the experience of opening up a package containing some new gadget they ordered. It’s like something happens, a YouTuber “watches” it happen while recording themselves watching, and then you watch the them watching, i.e. “reacting.” And of course you then react, too.

My first thought: this is so dumb. So artificially meta.

But you know? The other day I wrote about the importance of reception history for classic texts. Knowing how a classic text has been received down through the ages, from its original publication down to one’s own time, provides huge clues to how later readers themselves will read that text, the biases that are inherited, so to speak.

I mentioned that the term reception history is most often applied to biblical texts, though it can apply to anything. Just to take an obvious example of how future readers can be affected by reception history, note that it matters that original biblical manuscripts did not come divided into handy chapters and verses. That came later. The very structure of the text as received has been modified. Note also that the “Old Testament” (Hebrew scriptures) alone were in fact the Christian Bible for centuries before “New Testament” texts were definitively, canonically added. Debates are still going on, in fact, as to what exactly should be included in “The Bible,” even for Christians.1 Never mind differences in manuscript traditions and translations. Never mind Church-splitting, denominational interpretations of controversial verses.

Important texts come down to us brim full of built-in reactions to them. Whenever you read a classic text, or try to ferret out classic ideas, you’re watching and reacting to reactions.

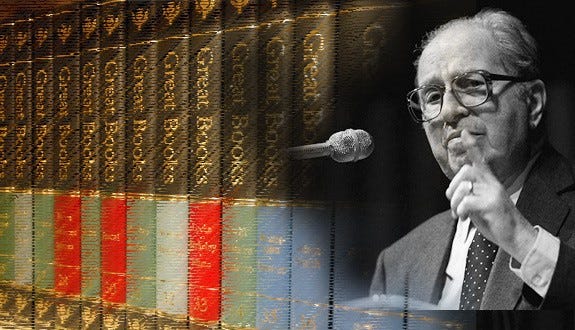

Today I want to react to an article (not exactly a classic) by Mortimer Adler — Mr. Great Books himself — having to do with The Problem of Education for our times. I want to appreciate his pedagogical rhetoric and attempt at policy wonkery, while also offering some constructive criticism. Adler is not wholly, but still quite badly, out of date.

The article in question is “The Schooling of a People,” found as a chapter in the collection edited by Geraldine van Doren, Reforming Education. It was originally published in 1957 with a revised version from 1976 included in the volume. The article includes an introduction to what Adler sees as The Problem, then six sections elaborating on the historical origins of the Problem (section 1), key educational principles coming from traditional educational theory (section 2), the American commitment to education overall but a tragic breakdown of implementation (sections 3 & 4), and Adler’s framing of choices to be made, enumerated in concrete K-12 options, plus his arguments about what should be done (sections 5 & 6).

Adler calls upon educators to appreciate the difficulty of solving the Problem, which in his day (and I would argue continuing even more so today), they neither recognize nor even vaguely appreciate in terms of its full scope and scale. I am answering Adler’s call to pay attention! Given the 50 years that have passed, it’s not surprising that I’ll have to disagree somewhat with his analysis, his enumeration of key choices, and some of his prescriptions. But there’s also a surprising extent to which I have to agree.

In a two-part essay, I’ll first review Adler’s intro and initial four sections, his set-up. In Part 2, coming soon, I’ll react to Adler’s proposals in sections 5 and 6 of his tract.

The Problem & its Historic Backdrop

Here’s Adler’s opening gambit: educators simply do not grasp the scale and scope of the educational problem now confronting us in a fundamentally new era.

With the advent of democratic institutions in the twentieth century, universal suffrage was established for the first time, and the distinction between a ruling and a subject class was abolished. With the maturation of industrial production in the last hundred years, human life and energy has at last been emancipated from grinding toil, and the distinction between a working class and a leisure class has been effaced. If the capitalist revolution in the next fifty years completes what the industrial revolution began, we can look forward to the first truly classless society in history — a politically classless society in which all men are citizens and members of the ruling class; and an economically classless society in which all men are capitalists and members of the leisure class.

It is the extraordinary difference between such a classless society, emerging now for the first time in history, and all the class-structured societies of the past, which helps us to understand why an industrial and truly capitalist democracy is confronted by a novel educational problem and one it will find so difficult to solve. This contrast between the classless society of the future and all the class-structured societies of the past also helps us to understand the nature and difficulty of that problem.

Source: “The Schooling of a People,” p. 115-116

Historically speaking, societies were all class-structured, and only a tiny segment of the human population had even the possibility of being part of an educated and ruling class. Why? Because before the industrial revolution, most people were necessarily involved in grinding toil. They labored, physically, all day, with no time for leisure, i.e. for non-physical (mental) activity. Industrialization changes all that. Machines can now do the back-breaking tasks. Fossil fuels provide energy that previously could only come from human or animal strength. Universal citizenship and the extension of suffrage in a democracy, and economic restructuring through industrialization and capitalism, changes everything. And this presents a huge educational opportunity — and challenge.

Adler goes on (sect. 1) to talk about the history of classical modes of education, which until about 1850 all shared remarkable continuity. Despite a couple of major crises, in the rise of Christianity during the transition from Greco-Roman antiquity, and during the Renaissance and Protestant Reformation — both having to do with the place of classical learning vis a vis the place of religion in society, and what emphasis to place on temporal vs. eternal goals for human life — there was still a single, constant thread prevailing. A Christian educational structure selectively saved and incorporated, and built upon, the classical, secular learning of pagan antiquity.

But all this changes.

Only with a sense of that continuity of Western education from the Greeks to the nineteenth century can we fully appreciate the sharpness of the break that has occurred since 1850.

Source: p. 117

One sees around that time, and in the American case as early as Thomas Jefferson, the emerging of a new idea, hitherto unthinkable — the idea that a society should be concerned with the education of all its people.

Jefferson, like all his predecessors, did not disagree that there was a fundamental division of “the mass of citizens” into the “laboring and the learned classes.” But he nevertheless proposed that all children — as citizens — should be given a minimum of three years of common schooling at the public expense. Adler counts this move as the “beginning of the democratic revolution.” (p. 117-118) Two further basic changes had to take place for this incipient revolution to come into full flower:

Two basic changes — in the constitution of government and in the production of wealth — had to take place before society was fully confronted with the problem of how to produce an educated people, not just a small class of educated men. The two changes, dynamically interactive at every point, were the extension of the franchise toward the democratic ideal of universal suffrage and the substitution of machines for muscles in the production of wealth.

Source: p. 118

This is as we have seen already. It turns out that these political and economic changes create both quantitative and qualitative challenges for education. First the “quantitative expansion” of education requires schooling not just for a small portion of the population, but for the people as a whole. Second, there’s also a “profound qualitative change in our culture” which, Adler says, reached its peak only in his day, even though a change had been set in motion from the seventeenth century.

We live in an age of science fully matured, an age of specialized research, dominated by the centrality of the scientific method and by the promises or threats of technology. Our educational problems are what they are — both in novelty and difficulty — because of the interplay of these two sets of factors: the quantitative extension of schooling to the whole population and the qualitative alterations in the content of schooling demanded by science and technology.

Source: p. 118-119

Clearly a lot has happened since Adler wrote in the mid-1950’s to 1970’s. Our political systems are not what they were in the early twentieth century with the extension of universal suffrage — however much still remained to be gained from the Civil Rights movement. Yet as a people, both in America and worldwide, we still struggle with exercising democratic privileges to vote, given today’s wide range of dubious electoral practices. We’ve also recognized that popular political power, however theoretically vested in voting citizens, means little in practice when legislative bodies, executive personalities and administrative bureaucracies, and even courts and the judiciary, are controlled or driven by influences well beyond any average citizen’s ken, much less any realistic ability to constrain or bend government to popular will.

Economically, it’s increasingly doubtful whether the economic boom of the mid-twentieth century following WW2, really allows the majority of people to be “capitalists” and enjoy true leisure (as if that’s what “capitalists” do), or whether not performing grinding physical labor all day doesn’t find a present analogy in an all-consuming addiction to screens and being perpetually tuned-in to an alternate electronic or virtual world.

Then there are all the scientific and technological changes Adler couldn’t even begin to fathom: the rise of the internet and vastly new means of global interconnectively and communication, a revolution in energy procurement and use, the globalization of trade and techniques, vast demographic changes… AI. The list is long.

Adler’s confidence in “the scientific method” is simultaneously on the wane. Now we know how politicized science, medicine, and “experts” in all areas have become. Haven’t we lost Adler’s naivete and general optimism regarding the promises (and the threats) of technology?2

Nevertheless, Adler has the basics of his problem correct. We can adapt his history to a more global and less myopically Western view. His accounts of fundamental change in politics and economics, culture and society map to a more up-to-date version of shifts in both human and planetary conditions as represented by the Anthropocene concept.

Adler’s Problem of Educational remains salient and massive in both quantitative and qualitative dimensions.

Educational Theory & Principles

Following a historical analysis of causes, Adler lays out his techne, his conceptual framework. He continues the reference to history, now the Great Books history of educational thought, by referring to the great philosophers, the “great contributors to educational theory” (Western style) in “Plato, Aristotle, Cicero, Quintilian, Augustine, Bonaventure Aquinas, Montaigne, Erasmus, Francis Bacon, Comenius, Locke, Rousseau, Kant, J.S. Mill, and Cardinal Newman.” (p. 119) Whatever their differences, these great thinkers all have a “notion of the controversial questions.”

With few exceptions, the differences of opinion [amongst these thinkers] tend to be more concerned with particular policies and practices than with general principles. The prevalence of common practices throughout the whole period during which schooling and education were restricted to the few, together with the sharing of basic theoretical insights, indicates a substantial agreement about general principles.

Source: p. 119

It’s odd that Adler says all these thinkers agree on general principles, but differ only on “particular policies and practices,” yet then he goes on to say there was a “prevalence of common practices throughout the whole period.” In any case, when educating only an elite few, even such a great diversity of thinkers differs only in minor points. Extending the list of names, if one considers philosophical thinkers also in eastern or Asian traditions, the point holds. Indeed, when educating an elite few, those who will rule and lead, who have enough leisure not to be encumbered all day by labor or work, there does seem to be a high level of agreement.

The question becomes: does the perenniel wisdom still hold, given the new quantitative and qualitative challenges?

Is it possible to educate a whole people,

given the radically new circumstances of the Anthropocene?

Adler sets up a philosophical framework for tackling the problem. He offers six general principles held in common by the educational tradition he reveres. For each principle, he invites educators to ask three questions:

Can we still affirm the truth of this principle, when the concern is with education for a whole people?

If we do affirm it, do we know how to apply it in practice, with results?

If we don’t affirm the principle, what new or adapted principle, will replace it?

Here are the six principles Adler lists (section 2, p. 120-121). Rather than type them all out, I’ll take a picture of the pages, so you can read them in full. It’s worthwhile to consider the long versions.

In short:

The aim of education is for the individual to live a good human life, both privately and publicly.

Basic schooling should be liberal, i.e. preparatory for a life of freedom, both political and economic, and there is no specialization at a basic level.

Basic schooling is preparatory (it equips) for lifelong learning, where lifelong learning is required for understanding and wisdom. Youth and immaturity are inherent limitations. (Basic schooling is not the same as specialized = professional schooling.)3

Society, including the state, both benefits from and should contribute to schooling and education. Society’s concern is not limited, however, to its own utility, but it exists for the broader perfection of human life.

Teachers require special (specialist) training in the liberal arts beyond the basics and must know what to teach as well as how to teach.

Scholars, who work best in community, contribute to the advancement of learning, which is essential to the vitality of education in any society.

Adler will focus on principles 1-4 in the rest of his article, especially as they concern “critical choices that confront us in the field of public education” (p. 121).

The American Commitment (& Failure)

We need not say overmuch about the following two sections. Adler seeks to establish through a series of quotations and anecdotes the commitment of the American democratic vision to public education (section 3). There seems little doubt about such a commitment, even continuing today.

However, he goes on (in section 4) to show how such a vision has hardly resulted in adequate progress towards the end in view, even amongst the most committed. The Problem of Education is not one of principles and theory only or primarily, but is equally one of implementation and practice, of actually achieving results. As of his own day, mid-20th c., Adler has seen some real progress, quantitatively. But even so, in perhaps what was the heyday of mass education in public schools in the US, what he sees is not enough.

The statements quoted and the views reported in the foregoing brief survey of the American commitment to universal public schooling [section 3] are submitted as a sketchy sampling of opinion from the beginning of the republic to the present day. They should not be read as accurately reflecting the facts of the school system, much less as giving us reliable appraisals of its effectiveness or accomplishments. They may generate the impression that, almost from the beginning, this country was dedicated to the schooling of all its children at the public expense, both for the perpetuation of our free institution and for their own fulfillment as human beings, but not until the present century—in fact, not until very recently [i.e. mid-20th c.]—have the number of children in our schools and colleges and the duration of their attendance at these institutions come near to approximating a system of universal education that looks as if it might be serving the aims which our ancestors had in mind.

Source: p. 125-126, opening of section 4

Until the turn of the century, whatever efforts had been made previously, “all or most or a majority of the children [who] had the benefit of primary or elementary schooling, could not be expected to achieve more than a rudimentary literacy and numeracy.” They had hardly been offered, in other words, anything close to the liberal education essential to a new democratic citizenry and leisured class — even if the leisure to engage in lifelong learning could be for only a few hours a day. They had hardly been offered an education

adequate to the task of producing an educated people—a citizenry or electorate capable of exercising a free and critical judgment on public issues and on the performance of public officials and a society of cultivated human beings, each of whom schooling had helped to realize his capacity for learning, each in a measure proportionate to the degree of his native endowment. Not until this century does the extension of schooling, both in the number of children it accommodates and in the number of years it provides instruction for them, reach a quantitative scope that warrants us in saying that we are now engaged in the schooling of a whole people.

Source: p. 126

Quantitative achivements not withstanding, Adler still questions the qualitative level that has been attained. It does not “remotely resemble what we have in mind when we contemplate the ideal of an educated people.”

There’s a striking discrepancy between the ideal envisioned, from the beginning, even committed to throughout the course of the American experiment, and the reality on the ground. If this was true then, in Adler’s day — whatever improvements were made in the 20th century — what about now? What’s our educational ideal? What have been our educational accomplishments and failures?

Starting in 1850 or thereabouts, following on from Thomas Jefferson’s first tentative enunciation of the new democratic principle of educating all people, some enormous strides have been made, at least in the US. But Adler’s questions and formulations of the Problem of Education remain: where are we, how did we get here, to what are we committed, and how will that vision be effectively realized?

To be continued in Part 2, forthcoming.

Compare, for example, Protestant vs. Roman Catholic vs. Eastern Orthodox vs. Ethiopian or Coptic versions of the Christian Scriptures. Look up terms such as “apocrypha” and “deutrocanonical.” Read about the formation of the biblical canon(s). From the perspective of the Hebrew scriptures (canonical for Jews), consider the differences between Greek Septuagint (older) vs. Masoretic text in Hebrew (more recent, but canonical).

The main threat of technology for those of Adler’s generation — we see this in Arendt, too — is the threat of nuclear war. Within a decade from the 1950’s, starting in the 1960’s, there is added a recognition of environmental problems: pollution, endangered species, and soon enough, escalating debates about climate change.

Lifelong learning as continual upskilling for the sake of job, career, or professional advancement would not count in Adler’s conception. He calls for lifelong learning as ongoing liberal education, for which basic schooling is preparatory, “learning how to learn.”

The main issue imo is that not all people want to be educated. Especially children, who without adequate supervision or parental indoctrination, can find sitting in a class room rather tedious. And then there are all the adults who somehow are still children and never really became adults, in that their minds are undisciplined and they enter into society unwillingly, and disinclined to accept any sort of adult responsibility. I guess what I'm saying is that before education, there must be adequate parenting.