With the shift to renewable energy, the world is hot on the trail of essential (often rare) metals needed for batteries and other technology components. At least a couple major news items have cross my radar recently, so I thought I’d share.

Lithium

Back when we lived in California, my husband worked for the state legislature doing policy analysis, including energy policy, especially hydro. The Salton Sea at that time (and since) was a highly controversial artificial lake that had become an environmental cause célèbre by attracting birds on the Pacific Flyway. More recently, it’s become known as “the biggest environmental disaster in California history” (Wikipedia, citing Palm Springs Life magazine, 2020).

Four years later, the sea has now been discovered to hold an immense store of lithium, one of the world’s largest.

The U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) recently revealed the results of an extensive analysis conducted by the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, unearthing an immense store of lithium beneath California's Salton Sea.

Termed the "Saudi Arabia of lithium" by Governor Gavin Newsom, the region's underground reservoir of scorching hot brine is now estimated to contain enough lithium to produce a staggering 375 million electric vehicle batteries.

This discovery positions the Salton Sea as one of the largest lithium brine deposits globally, promising a seismic shift in America's approach to lithium production.

(Source: A hidden deposit of lithium in a US lake could power 375 million EVs (interestingengineering.com))

MotorBiscuit has the story of GM’s investment in the extraction project, along with some disturbing recent pictures.

By way of comparison, here’s a map of lithium mines worldwide:

Copper

In a separate discovery, California-based startup KoBold Metals, backed by Bill Gates, Jeff Bezos, and other billionaires, has confirmed a huge copper deposit in Zambia. The company uses AI, satellite imagery, and big data analysis to locate new mineral worldwide.

Using artificial intelligence, Kobold aims to create a “Google Maps” of the Earth’s crust, with a special focus on finding copper, cobalt, nickel and lithium deposits.

It collects and analyzes multiple streams of data — from old drilling results to satellite imagery — to better understand where new deposits might be found.

Algorithms applied to the data collected determine the geological patterns that indicate a potential deposit of cobalt, which occurs naturally alongside nickel and copper.

The technology, KoBold said, can locate resources that may have eluded more traditional geologists and can help miners decide where to acquire land and drill.

(Source: KoBold says Zambia copper find largest in a century - MINING.COM)

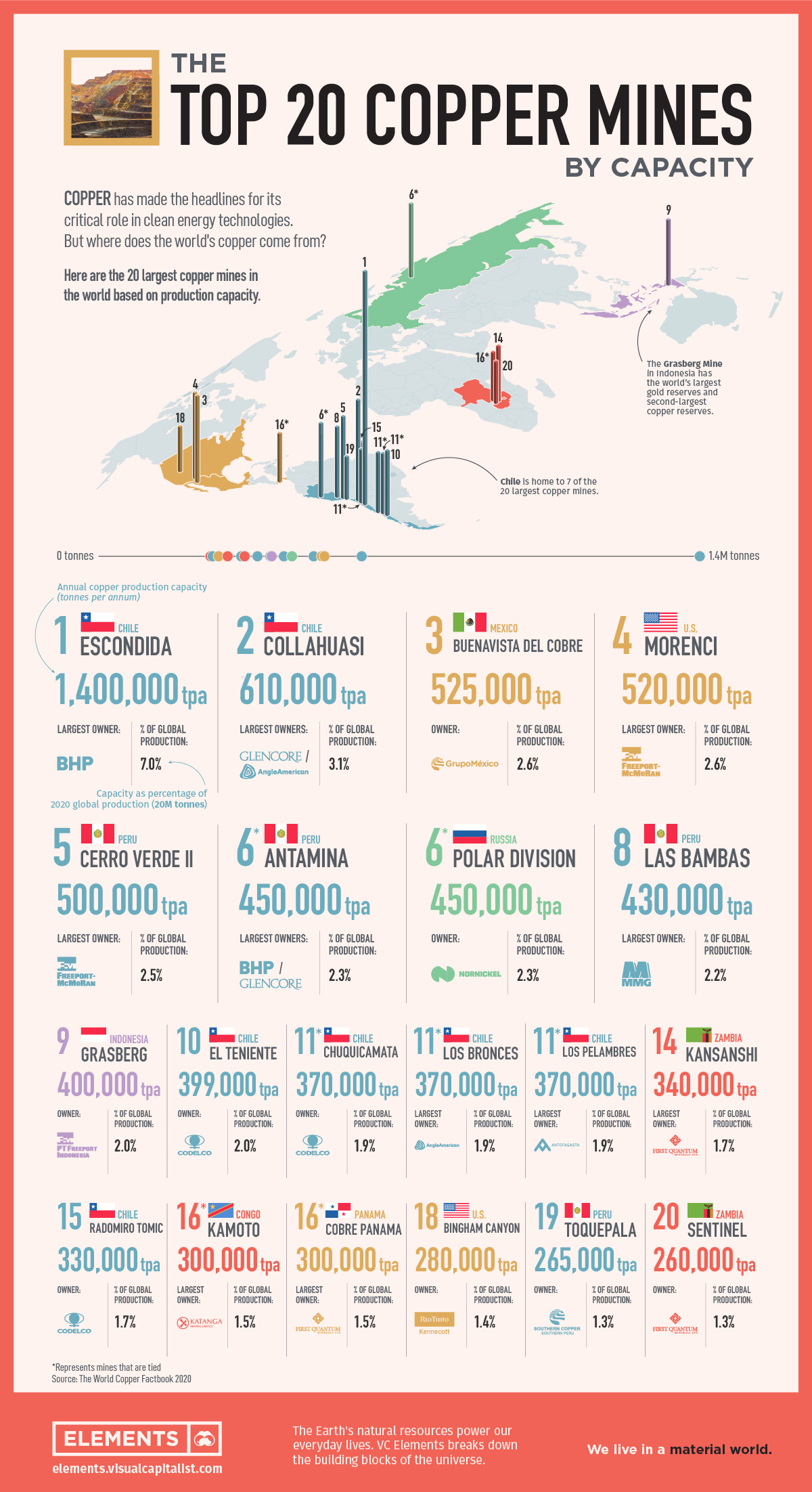

Looking for copper worldwide? Here it is:

And if you want to see what it’s like to work at the largest copper mine in the world:

Cement & Turquoise

I have cement and turquoise mines in my neighborhood. I live near the intersection of Highway 40 and the Turquoise Trail (Hwy 14) in New Mexico. There’s a huge cement factory and mine just south of Tijeras, right in the pass. It’s an eyesore and visible from every elevation in the area, including my backyard deck. The plant is undoubtedly the largest employer in Tijeras, and the company that runs it, along with four others from Montana to Texas, produces 3.5 million tons of ready-mix concrete.

Here’s what the land scars look like on Google maps.

If, on the other hand, you drive north towards Cedar Crest, through Madrid and Cerrillos, all the way up to Santa Fe, you’re driving the Turquoise Trail, a historic route, now attracting mostly tourists. The route originally gave access to miles of turquoise mines scattered along the way. It is a scenic drive, but you can definitely see old scrap heaps and scars from the roadside.

I stand on a hill a few miles north of the village of Cerrillos. Broken wagon wheels and scrubby green piñon trees hold close to the land. Santa Fe jeweler Douglas Magnus has met me here to show me the famed Tiffany-associated mines that he stewards. “The Tiffany company is responsible for getting turquoise noticed and giving it value. They increased respect for both the material and the American role in design and production,” he says. Magnus looks like he stepped out a modern Western, like a turquoise-mining Sam Elliot. A string of silver skulls circles his wrist.

From the late 1800s into the early 1900s, miners sorted through the rocks here, seeking perfect clear robin’s egg blue gems to match Tiffany’s signature color. Most weeks, a cigar box full of rough stone traveled by train from Cerrillos to back east and into the hands of jewelers trying to meet the demand of a burgeoning market. “It’s been an enormous honor in my life experience to be associated with these mines,” Magnus says.

(Source: On the Turquoise Trail (newmexicomagazine.org))

What’s in your backyard?